Metallosis is a

syndrome associated with metal

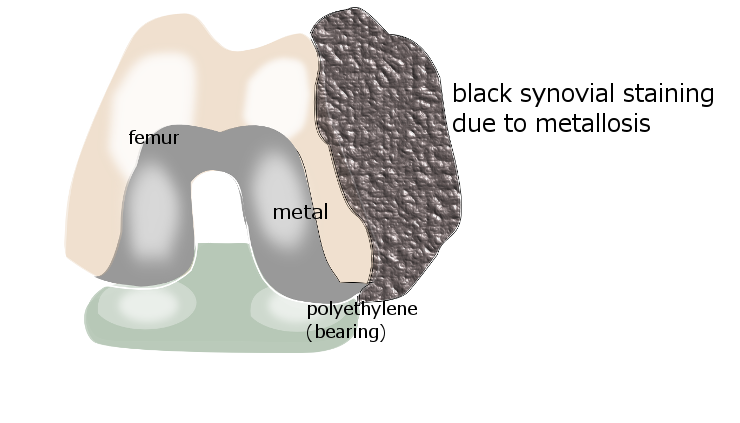

joint implants, where friction between two metal surfaces releases metal ions (electrically charged particles) into the joint, and these trigger an inflammatory response. The term 'metal-induced

synovitis' describes those parts of the

synovial joint lining that bloat up and become rubbery and filled with a florid black staining due to the metal ions.

Within the knee this condition is usually related to a previous knee replacement (usually a

total knee replacement, but also sometimes in a partial/

unicompartmental1 knee replacement) in which the

polyethylene components have worn down and inadvertently allowed metal components to come into contact where they normally would not. In particular it is often the polyethylene part of the metal-backed

patella that is at fault, where the polyethylene breaks down and allows the back of the

patellar component to make friction contact with the metal femoral component

2. Metal-backed patellar components are no longer in frequent use but of course there are still many patients who had had this type of implant done in previous years. Mechanisms of failure of the polyethylene include polyethylene wear,

fracture of the polyethylene or the underlying bone, and dissociation of the polyethylene from its metal backing.

The condition is more frequently recognised in hip replacements. Although rare in the knee, metallosis is a diagnosis must be thought of when investigating a patient whose knee is not settling after a knee replacement

Components of a knee replacement

Knee replacements are not all the same. Different manufacturers have their own designs, materials and components, and the surgeon will make his choice among their products based on his/her assessment of the patient's needs and his/her own

clinical experience. However, most knee replacements contain -

- a metal femoral component

- a metal tibial component

- a 'bearing' between them of high density polyethylene, which may be mobile or attached to the tibial component

- a patellar component of polyethylene or metal-backed polyethylene

In uncemented components there may be coatings of various kinds at the back of the components to encourage bone adhesion.

The metals from which the implant is manufactured may include3 -

- titanium and titanium alloys

- cobalt and cobalt-chrome alloys. Cobalt chrome alloys contain a nickel component, which is very relevant in people who are allergic to nickel.

- zirconium and zirconium alloys

- ceramics including oxidised zirconium

- tantalum

Hip implants may be metal-on-polyethylene, metal-on-metal, metal-on-ceramic or ceramic-on ceramic, but most knee implants are metal-on-polyethylene. The issue of metal-on-metal designs is current and controversial4. Several hip implant manufacturers have recalled their metal-on-metal implants5, and patients who have already received such implants are carefully monitored and may be subjected to additional surgery to replace them

In the knee, which is what we are talking about here, we are not talking about metal-on-metal designs but to inadvertent metal/metal contact due to failure of the polyethylene bearing between the metal components. The metal ions thereby released may cause both local and wider (

systemic) symptoms.

Local and systemic effects of metal toxicity

There seems to be two types of problems related to the situation we are discussing. On the one hand the polyethylene wear leaves real particulate debris of polyethylene, which is taken up by the lymph cells and transported to the lymph glands. As the body tries to rid itself of these particles a process called '

osteolysis' may occur, where bone is broken down and weakened in areas around the implant. This can be seen on X-ray or CT imaging.

On the other hand, the breakdown of the polyethylene may distort the mechanics of the implant and allow metal to come into contact with metal. The resultant friction may release charged metal ions, which are not the same as the particulate matter of the polyethylene, although sometimes, but rarely, there may be actual metal particles. The presence of metal ions can be inferred from X-ray changes which we will discuss later.

The breakdown of the polyethylene may affect the mechanics of the implant, the osteolysis may allow loosening of the implant, the debris may bring other inflammatory-response cells into the area which will be releasing chemicals of their own. The metal ions are taken up by the

synovium(the joint lining), which may become abnormal - bloated in patches and filled up with grey-black staining. Uptake by histiocytes

1 may affect regional lymph glands, and metal ions in the bloodstream may cause metal toxicity.

The combination of all of these factors may lead to2 -

- severe knee pain and quite marked knee swelling, with excessive fluid in the joint

- crepitus, and feelings of instability associated with loosening of the implant

- pseudotumours6

- fractures around the implant

- skin rashes, confusion, tinnitus, deafness, and even dementia.

Some patients may have a frank allergy to certain metals, eg nickel,cobalt and chrome while in other patients it may be more a matter of metal toxicity. Skin patch testing may differentiate between the metals, although it may be necessary to do blood tests and histology on the lymph nodes. Potentially the most harmful components are cobalt from cobalt-chromium alloy, nickel from stainless steel, and vanadium from titanium alloy7.

X-rays may show excessive fluid within the joint, osteolysis around the implant. The joint lining and

suprapatellar pouch may show a fine linear radio-opacity called a 'metal-line. Other radiographic signs called 'clouds' and 'bubbles'

2 may be indicative of the metal within the synovium as well as the florid synovial outgrowth, seen during surgery as areas of joint lining (synovium) heaped up into what look like soft black lumps.

Blood levels

It would seem logical to simply monitor knee replacement patients for raised metal levels, but this is not as simple as it seems. The biggest culprit for toxicity seems to be cobalt-chrome but there is no generally accepted threshold beyond which serum or blood concentrations of cobalt and chromium are known to be toxic

8. Despite this, it appears that a

revision from a cobalt-chrome

femoralcomponent to a ceramic one, or replacement of a metal-backed, with a polyethylene patellar component should be contemplated when there appears to be toxicity problems

9.

Ceramic components appear to offer advantages, but the long term outcome is still being evaluated10.

References

9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23590796Thakur RR, Ast MP, McGraw M, Bostrom MP, Rodriguez JA, Parks ML. Severe persistent synovitis after cobalt-chromium total knee arthroplasty requiring revision. Orthopedics. 2013 Apr;36(4):e520-4. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130327-34.

10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22582104Bergschmidt P, Bader R, Ganzer D, Hauzeur C, Lohmann C, Rüther W, Tigani D, Rani N, Prats FL, Zorzi C, Madonna V, Rigotti S, Benazzo F, Rossi SM, Kundt G, Bloch HR, Mittelmeier W. Ceramic femoral components in total knee arthroplasty - two year follow-up results of an international prospective multi-centre study. Open Orthop J. 2012;6:172-8. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010172. Epub 2012 Apr 20.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Sheila Strover is the founder of the KNEEguru website. Although not a

knee surgeon, she has a sound understanding of

knee surgery and...